May not know that in Spain, between one third and nearly half of adults have hypertension. This means that between 1 and 2 out of every 4 people have high blood pressure—although they may not always be aware of it.

And may also not know, or may not be fully aware, that—much like diabetes mellitus—arterial hypertension (HTN) is one of the main “silent killers” affecting our society. It often causes no symptoms, yet it gradually damages our blood vessels and internal organs, increasing the risk of serious and potentially fatal complications. Every millimeter of mercury (the unit used to measure blood pressure) that is brought under control represents time gained and health preserved. Would you like to learn why this is so?

Dr. Minguito – Neolife Medical Team

What Is Arterial Hypertension?

Arterial hypertension is one of the leading cardiovascular risk factors in our society. At Neolife, we aim to provide you with a clear perspective so you can understand what it is, why it is so important to keep it well controlled, and what poor control can lead to. Here’s a spoiler: if you care about your brain, your heart, and your kidneys, you need low blood pressure.

When we talk about blood pressure, we are referring to the force exerted by the blood against the walls of the arteries as the heart beats. We have all heard, during a doctor’s visit, two measurements: the “upper” and the “lower” numbers—but what do they actually mean?

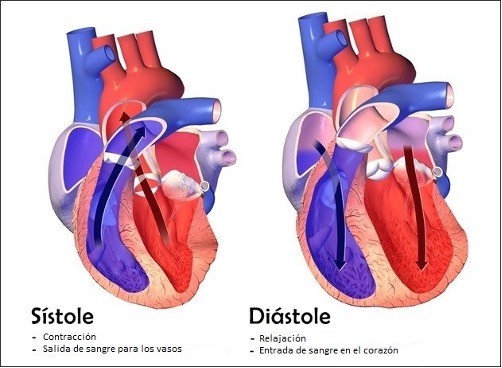

The cardiac cycle has two main phases: systole and diastole. During systole, the heart’s ventricles (the lower chambers) contract to eject blood. The left ventricle is especially important in this process because it is more muscular than the right and is responsible for pumping blood throughout the body, overcoming the resistance of the peripheral circulatory system.

It is worth noting that here we are referring to systemic or peripheral circulation—the circulation that supplies the body in general—and not to pulmonary pressure, which is a different measurement. Blood pressure, commonly reported as “120 over 80,” refers to pressure in the peripheral circulation. Pulmonary pressure, which is mainly regulated by the right ventricle, is considerably lower.

During systole, the left ventricle contracts and pushes blood out of the heart through the aortic valve into the aorta (the large artery leaving the heart), from where it is rapidly distributed throughout the body. In this phase, the blood exerts pressure against the arterial walls—this is the systolic pressure (the “upper” number).

The second phase of the cycle is diastole, which is equally important. During diastole, the heart relaxes after ejecting blood, allowing the ventricles to fill again from the atria. This is also the phase during which the heart itself receives its blood supply through the coronary arteries. Although blood pressure is lower during diastole, there is still a constant or tonic pressure within the arteries—this is the diastolic pressure (the “lower” number).

What Does It Mean to Have High Blood Pressure, and Why Is It So Important to Keep It at Optimal Levels?

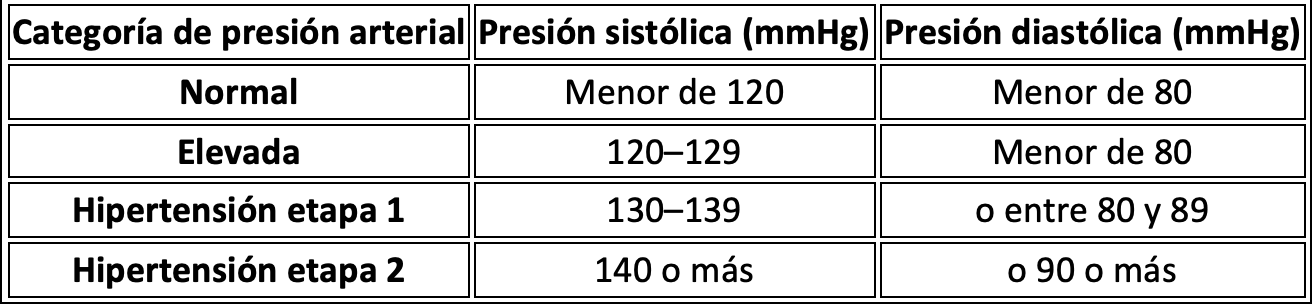

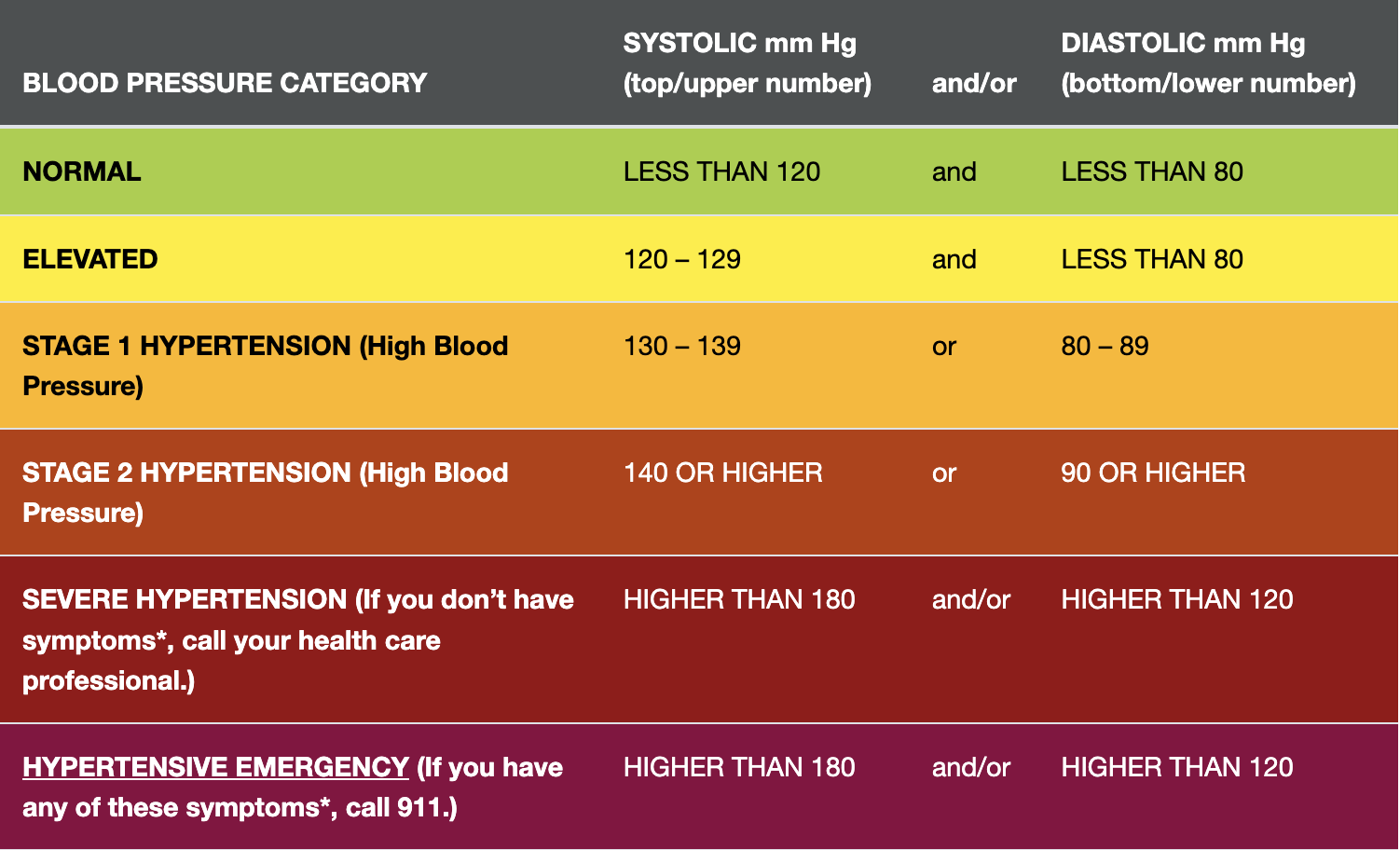

Since 2017, guidelines have changed following the publication of the SPRINT clinical trial (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) in 2015. Current recommendations, in effect for approximately six years, establish new blood pressure categories.

Blood pressure classification (according to current guidelines)

For example, a person with a blood pressure of 120/83 mmHg would already fall into the category of stage 1 hypertension, even though their systolic pressure remains within the traditionally “normal” range.

Where Do These Values Come From? The SPRINT Trial (2015)

The aim of the SPRINT study was to evaluate the benefits of intensive blood pressure control. Nearly 10,000 individuals with a systolic blood pressure of 130 mmHg or higher and a high cardiovascular risk—but without type 2 diabetes—were included. This population was selected because a higher probability of cardiovascular events over a short period was expected, making it easier to assess clinical outcomes.

Participants were randomly assigned to two groups:

- Intensive treatment: target systolic blood pressure below 120 mmHg.

- Standard treatment: target systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg.

At baseline, the average blood pressure of participants was approximately 140/78 mmHg. After one year of treatment, average systolic blood pressure was 121.4 mmHg in the intensive-treatment group and 136.2 mmHg in the standard-treatment group.

The most striking aspect of the study was that it was stopped early due to the clear clinical benefits observed in the intensive-treatment group. The most notable finding was a reduction in all-cause mortality—not only from cardiovascular causes, but also from kidney disease, accidents, suicides, and even homicides. This benefit was unexpected and surprised many experts.

This study was one of the most compelling demonstrations that intensively controlling systolic blood pressure below 120 mmHg can save lives and reduce cardiovascular events, even over a relatively short period.

The study also reminds us that conditions such as hypertension, smoking, and elevated apoB levels (a marker of atherogenic cholesterol) cause cumulative damage over time. Hypertension mechanically damages the vascular endothelium, smoking causes chemical damage to the same tissue, and LDL cholesterol (which contains apoB) infiltrates the damaged endothelium, initiating the atherosclerotic cascade. For this reason, early reduction of all these risk factors has an enormous cumulative effect over time.

Years later, in 2021, the STEP study in China once again demonstrated that strict blood pressure control reduces cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality.

We may still hear—or hold on to—the outdated belief that a blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg is acceptable. However, in light of all this evidence, it is clear that this is not the case. We need to change our mindset and pursue intensive control, aiming for a target of approximately 120/80 mmHg.

As early as the 1960s, the first data from the Framingham Heart Study had already shown the harmful effects of elevated blood pressure (at that time, hypertension was defined as any value above 140/90 mmHg). Lowering blood pressure from levels above that threshold already demonstrated clear benefits.

More recently, other meta-analyses have confirmed these findings. In individuals aged 40 to 70, for every 20 mmHg increase in systolic pressure or 10 mmHg increase in diastolic pressure, the risk of death from heart attack, stroke, or vascular disease doubles. This refers not only to a higher incidence of disease, but to a higher probability of death. For example, having a blood pressure of 140/90 instead of 120/80 doubles the risk of vascular death.

Other Organs Affected

The heart is not the only organ sensitive to hypertension. The brain is particularly vulnerable to high blood pressure, as both depend on proper perfusion through small vessels. Hypertension exerts a mechanical force that damages these vessels, increasing the risk of stroke and dementia.

The SPRINT-MIND trial, a substudy of SPRINT focused on cognitive decline, evaluated whether intensive treatment could prevent dementia. With more than 9,000 participants, the results showed an absolute reduction in dementia risk of 0.6% and a relative reduction of 16%. Thus, controlling blood pressure protects the brain.

The kidneys are another organ extremely sensitive to elevated blood pressure. Despite accounting for only 1–2% of body weight, they receive 20–25% of cardiac output (the amount of blood the heart pumps each minute to deliver oxygen and nutrients throughout the body). This implies a highly specialized and vulnerable vascular network. Hypertension accelerates the decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), reducing kidney function.

The situation worsens when elevated glucose levels are also present—a common combination, for example, in metabolic syndrome (which includes hypertension and insulin resistance). This leads to a progressive and dangerous decline in kidney function, often undetected if only creatinine is measured. For this reason, at Neolife, when kidney function impairment is suspected, we use cystatin C, a more sensitive marker.

The key message from these studies is that lowering blood pressure—even in individuals already diagnosed with hypertension—can significantly reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other serious health conditions. While preventing blood pressure elevation in the first place is ideal, these trials show that reducing blood pressure after it has already exceeded optimal ranges still offers enormous cardiovascular benefits.

Caution: Low Blood Pressure, but Not Too Low

While high blood pressure is dangerous, excessively low blood pressure can also cause problems—although in this case, symptoms matter more than numbers. Technically, low blood pressure is defined as below 90/60 mmHg, but what truly matters is how the person feels.

Common symptoms of low blood pressure include dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, fainting or syncope, dehydration or excessive thirst, difficulty concentrating, blurred vision, cold and pale skin, rapid and shallow breathing, and fatigue.

Not everyone with low blood pressure experiences symptoms. Some people may feel perfectly well with readings such as 100/70 mmHg, while others may not tolerate these levels, especially if they have lost weight or are taking antihypertensive medications.

For this reason, blood pressure management requires a personalized approach. As weight is lost, exercise increases, or other factors change, blood pressure may decrease naturally, and medications must be carefully adjusted to avoid adverse effects such as fainting or loss of balance.

Blood Pressure Variations Throughout the Day and With Exercise

Blood pressure naturally fluctuates throughout the day. A key observation is that during the night, it should decrease by 10–20% compared to daytime values. This is partly due to the horizontal position during sleep, which reduces the effort the heart needs to send blood to the brain. Additionally, sympathetic tone (the body’s “alert” system) should decrease at night, while parasympathetic tone—especially vagal activity—increases, promoting relaxation. Continuous blood pressure monitoring seeks precisely this nocturnal dip as a marker of cardiovascular health.

Stress also plays an important role. Transient stressful events can significantly raise blood pressure. Leaving excess cortisol (hypercortisolemia) uncontrolled can be just as harmful as persistent hypertension.

It is completely normal for systolic blood pressure to rise during exercise, as the heart needs to pump more blood to deliver oxygen to the muscles. In contrast, diastolic pressure usually remains stable or decreases slightly. This occurs because, during exercise, blood vessels in the muscles dilate (vasodilation), reducing resistance in the circulation. Thanks to this mechanism, exercise acts as a natural regulator of blood pressure: it improves arterial elasticity, reduces vascular resistance, and over time helps control resting blood pressure.

Primary vs. Secondary Hypertension

Another important concept is that hypertension may be due to an identifiable cause—this is known as secondary hypertension. It is caused by an underlying medical condition that may potentially be corrected. It is estimated that about 10% of hypertension cases have a secondary cause, so it is important not to assume that all hypertension is “essential” or primary.

There are warning signs that suggest secondary hypertension, such as lack of response to medications, loss of response to previously effective treatments, extremely high blood pressure (above 180 mmHg), or sudden onset. It is also suspicious when a young person with no family history or risk factors develops high blood pressure.

Other secondary causes that should not be overlooked include kidney disease, renal artery stenosis, thyroid disorders, sleep apnea, and hyperaldosteronism (which may result from prolonged corticosteroid use or adrenal gland disorders), among others.

At Neolife, we believe that blood pressure management is one of the most important pillars of longevity. It may not sound as glamorous as the latest anti-aging treatments, but it is one of the most effective and well-proven strategies in preventive medicine to reduce morbidity and mortality.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Banegas JR, Graciani A, López-García E, et al.

Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Spain: results of a nationwide population-based study.

Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2024;224(2):83–92.

Disponible en: PubMed.

(2) Rodríguez-Roca GC, Coca A, Barrios V, et al.

Guía práctica sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la hipertensión arterial en España.

Hipertens Riesgo Vasc. 2022;39(4):155–170.

Disponible en: Elsevier.

(3) Camafort M, Gijón-Conde T, Segura J, et al; IBERICAN Study Group.

Prevalence and control of hypertension in primary care: results from the IBERICAN study.

Eur J Gen Pract. 2024;30(1):1–10.

Disponible en: PMC.

(4) Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN).

Nota de prensa Día Mundial de la Hipertensión 2024.

SEMERGEN; mayo 2024. Disponible en: SEMERGEN PDF.

(5) Banegas JR, et al.

Prevalence of hypertension in Spain 2019: population-based nationwide study.

J Hypertens. 2024;42(3):431–440.

Disponible en: ScienceDirect.

(6) SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al.

A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control.

N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

(7) Zhang W, Zhang S, Deng Y, et al; STEP Study Group.

Trial of intensive blood-pressure control in older patients with hypertension.

N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1268–1279.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2111437

(8) Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al.

2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248.

(9) Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM.

Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

2003;42(5):878–884.

(10) He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA.

Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials.

2013;346:f1325.

(11) Huang L, Trieu K, Yoshimura S, et al.

Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials.

2020;368:m315.

(12) Brouillard AM, Kraja AT, Rich MW.

Trends in dietary sodium intake in the United States and the impact of USDA guidelines: NHANES 1999–2016.

Am J Med. 2019;132(10):1199–1206.e5.

(13) Cornelissen VA, Smart NA.

Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1):e004473.

(14) Carnethon MR, Gidding SS, Nehgme R, Sidney S, Jacobs DR Jr, Liu K.

Cardiorespiratory fitness in young adulthood and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors.

2003;290(23):3092–3100.

(15) Kang DO, Lee DI, Roh SY, et al.

Reduced alcohol consumption and major adverse cardiovascular events among individuals with previously high alcohol consumption.

JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e244013.

(16) Miller PM, Anton RF, Egan BM, Basile J, Nguyen SA.

Excessive alcohol consumption and hypertension: clinical implications of current research.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(6):346–351.

(17) Han B, Chen WZ, Li YC, Chen J, Zeng ZQ.

Sleep and hypertension.

Sleep Breath. 2020;24(1):351–356.

(18) Li H, Ren Y, Wu Y, Zhao X.

Correlation between sleep duration and hypertension: a dose-response meta-analysis.

J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33(3):218–228.

(19) Agras WS.

Behavioral approaches to the treatment of essential hypertension.

Int J Obes. 1981;5 Suppl 1:173–181.

(20) Kennedy MD, Galloway AV, Dickau LJ, Hudson MK.

The cumulative effect of coffee and a mental stress task on heart rate, blood pressure, and mental alertness in caffeine-naïve and caffeine-habituated females.

Nutr Res. 2008;28(9):609–614.

(21) Steffen M, Kuhle C, Hensrud D, Erwin PJ, Murad MH.

The effect of coffee consumption on blood pressure and the development of hypertension.

J Hypertens. 2012;30(12):2245–2254.

(22) Kim JA, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ.

Reciprocal relationships between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: molecular and pathophysiological mechanisms.

2006;113(15):1888–1904.

(23) Medrano MJ, Cerrato E, Boix R, Delgado-Rodríguez M.

Cardiovascular risk factors in Spanish population: metaanalysis of cross-sectional studies.

Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124(16):606–12. doi:10.1157/13074389.

(24) Tormo MJ, Navarro C, Chirlaque MD, Pérez-Flores D.

Prevalence and control of arterial hypertension in the South-East of Spain: a radical but still insufficient improvement.

Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13(3):301–8. doi:10.1023/A:1007341404633.

(25) Gutiérrez-Misis A, Sánchez-Santos MT, Banegas JR, et al.

Prevalence and incidence of hypertension in a population cohort of people aged 65 years or older in Spain.

J Hypertens. 2011;29(10):1863–70. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834ab497.