Bacterial overgrowth or SIBO is characterized by an excess of colonic flora in the small intestine, causing various digestive symptoms and in some more severe cases, symptoms of malabsorption.

Gut flora comprises a complex ecosystem, composed of over 500 different bacterial species that colonize the digestive tract from birth and maintain a relatively stable composition throughout life.

Dr. Débora Nuevo Ejeda – Neolife Medical Team

What happens when bacteria in the colon invade the small intestine?

Bacterial overgrowth or SIBO is characterized by an excess of colonic flora in the small intestine, causing various digestive symptoms and in some more severe cases, symptoms of malabsorption.

Gut microbiota: a complex ecosystem

Gut flora comprises a complex ecosystem, composed of over 500 different bacterial species that colonize the digestive tract from birth and maintain a relatively stable composition throughout life.

Such is the number and diversity of this microbiota that the bacteria present in the intestinal tract are much more numerous than the eukaryotic cells.

The stomach and small intestine harbor a fairly small amount of bacteria due to gastric acids and the effects of peristalsis.

Lactobacilli, enterococcus, aerobic gram positive bacteria, and facultative anaerobes are those that predominate in the jejunum and do not exceed 104 organisms/ml.

Bacteroides are the most abundant in the colon and are not often found in the small intestine.

The terminal ileum represents an intermediate area between the aerobic flora of the stomach and the small intestine and the anaerobic microorganisms of the colon. When the ileocecal valve is dysfunctional or surgically removed, the terminal ileum is very similar microbiologically speaking to the colon.

Epidemiology: Who are most susceptible?

The prevalence of SIBO is not entirely clear and depends on the population studied, and especially the method used in diagnosis.

What seems to be clear is that the elderly population may be particularly susceptible, mainly because of their lower level of stomach acid and the consumption of certain drugs that may cause hypomotility. The lower level of stomach acid may be a major cause of hidden malabsorption in the elderly.

Also, pathologies like chronic pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and intestinal motility disorders are associated with up to 90% of cases of SIBO.

Causes: What are the risk factors for SIBO?

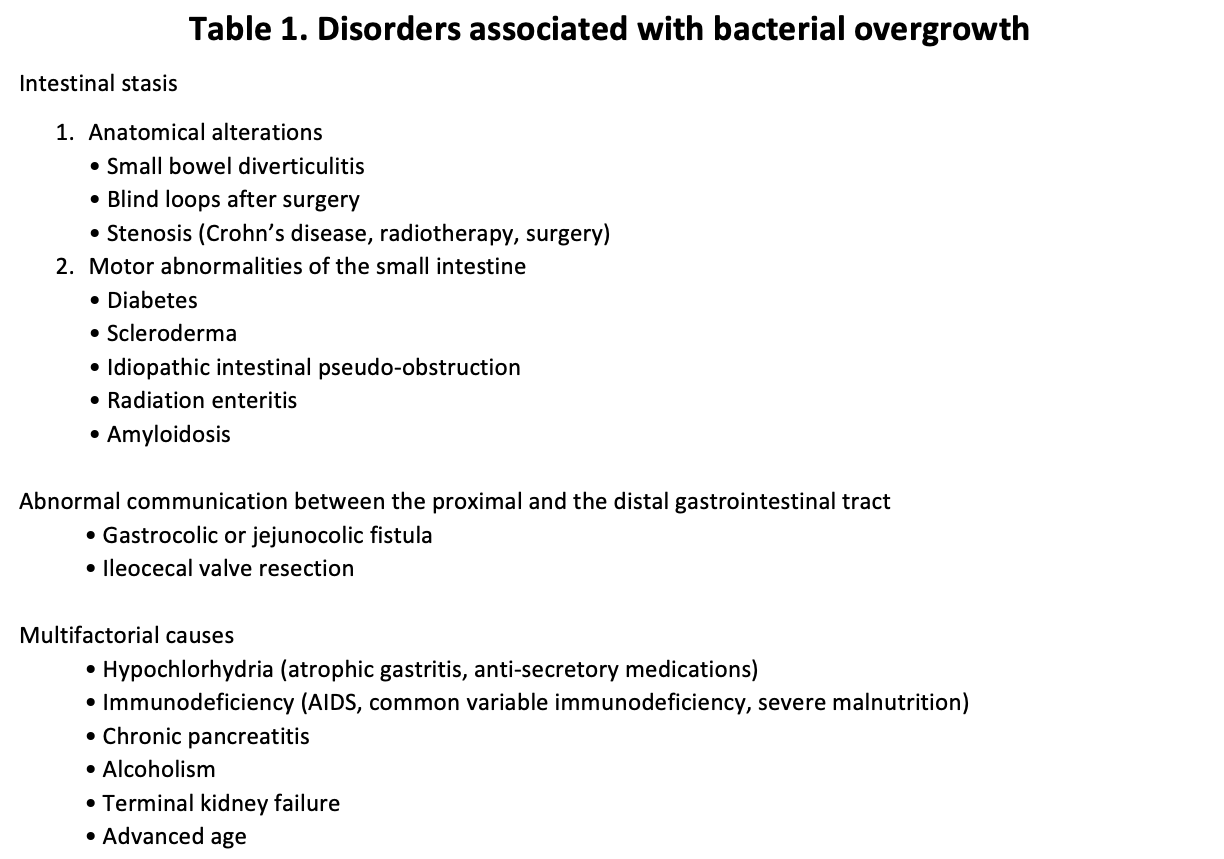

There are several conditions that predispose individuals to SIBO because they alter the defenses of the intestinal mucosa.

- Motility disorders: In the small intestine, the propulsive forces and especially phase II of the migrating motor complex limits the ability of bacteria to colonize some parts of the intestine. This motility may be disrupted by radiation enteritis, amyloidosis, or scleroderma. But it’s also present in disorders as common as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, or neuropathy, which accompanies Parkinson’s disease. It is also worth mentioning celiac disease in this section, as the chronic inflammatory state of the mucosa hinders intestinal clearance. This may be why some patients who do not respond to a gluten-free diet eventually improve after administration of intermittent doses of antibiotics.

- Breaking down of anatomical barriers: either due to surgery (such as the removal of the ileocecal valve or a gastric bypass in the treatment of obesity) or other disorders, such as the appearance of enterocolic fistula (the most common case is Crohn’s disease), small bowel tumors, diverticulosis or volvulus.

- Metabolic and systemic disorders: In addition to the aforementioned neuropathy of diabetes or hypothyroidism, disorders such as pancreatic insufficiency, cirrhosis, and fatty liver may lead to bacterial overgrowth.

- Immune disorders: Immunoglobulins present in intestinal secretions are essential to maintaining the balance and homeostasis of the microbiota. Patients with IgA deficiency, common variable immunodeficiency, or acquired immunodeficiency (e.g. HIV) may have a significantly higher risk of SIBO.

Physiopathogenesis: effects of SIBO on the intestinal mucosa and systemic repercussions.

The impairment of the absorption of nutrients may be attributed to the damage caused by the bacterial flora on the enterocyte through the adhesion of bacteria, production of enterotoxins, and the effect of the production of deconjugated bile acids such as lithocholic acid.

-

Carbohydrate malabsorption basically responds to two mechanisms: on the one hand, the intraluminal degradation of sugars leads to the production of short-chain fatty acids that increase the osmolarity of intestinal fluid, leading to diarrhea. And on the other hand, the damage of the enterocyte leads to disaccharidase deficiency. Unabsorbed sugars are fermented by bacteria producing high amounts of gas (CO2, H2, and methane) that lead to flatulence and bloating.

- Malabsorption of fats: Excess bacteria from SIBO in the small intestine deconjugate bile salts, leading to their absorption in the jejunum. This makes the concentration that reaches the intestinal lumen of more distal parts insufficient, causing steatorrhea and loss of fat-soluble vitamins. Additionally, free bile acids exert a toxic effect on the mucosa by increasing the secretion of water and electrolytes into the intestinal lumen, hence the watery nature of diarrhea in these cases.

- Protein malabsorption: the damage to the intestinal epithelium leads to a deficit in the production of amino acids, and some protein precursors present in the intestinal lumen are degraded by bacteria. This leads to an, in principle, reversible protein-losing enteropathy associated with SIBO.

Clinical, analytical, and endoscopic manifestations

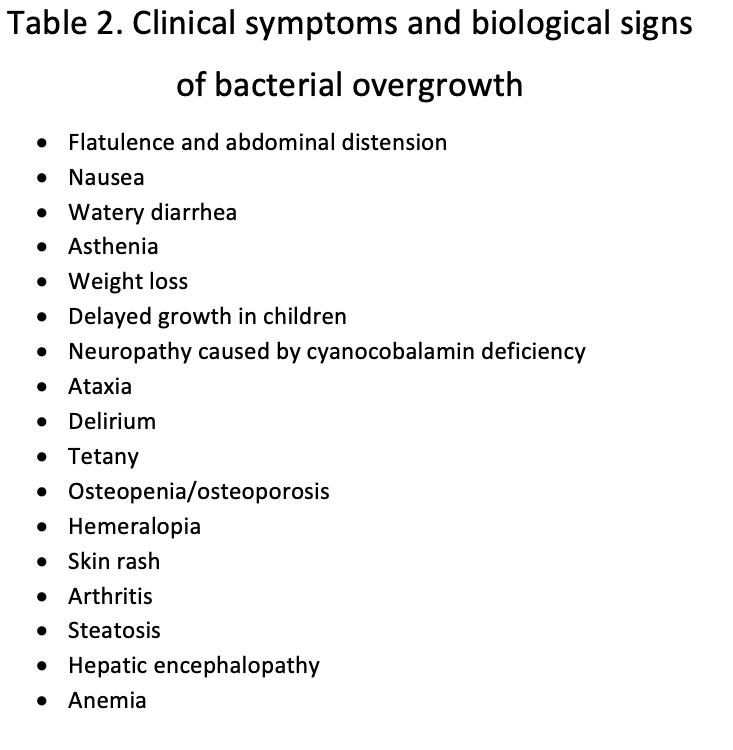

Symptoms may vary from a simple weakness to a motley syndrome of malabsorption.

The most typical symptoms are diarrhea, often steatorrhea (very abundant, sticky, and bright stools), bloating and abdominal pain, postprandial fullness, and weight loss.

We may also find symptoms derived from vitamin deficiencies, such as macrocytic anemia or sensory ataxia and paresthesia in the most severe cases of vitamin B12 deficiency. Hypocalcemia may cause perioral paresthesia or muscle cramps, and vitamin D deficiency may cause bone metabolism disorders. In extremely severe cases, alterations in the mental state associated with lactic acidosis have been reported after a meal especially rich in carbohydrates.

<p style=”text-align: justify;”Among blood test findings, it is not uncommon to find macrocytic anemia, low levels of vitamin B12 , thiamine and niacin, and high levels of folate or vitamin K. In rarer cases, microcytic anemia may be secondary to bleeding from small ulcers or when associated with ileitis or colitis.

Patients with protein-losing enteropathy may also present microalbuminemia.

Endoscopy results are usually quite non-specific; only in some severe cases, there may be evidence of associated colitis or ileitis. From an anatomopathological standpoint, there are no specific data, but in some cases, there may be eosinophilia, cryptitis, a flattening of intestinal villi, or intraepithelial lymphocytes.

How do we diagnose SIBO?

We should suspect SIBO in patients who present abdominal swelling, flatulence, intestinal discomfort, and chronic diarrhea.

Diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hydrogen breath test or a bacterial concentration that is greater than 10 3 colony forming units/ml in the jejunum. Hydrogen breath tests are usually preferred because they are simpler, non-invasive, and more economical.

- Hydrogen breath test

The test is conducted through the administration of a carbohydrate (lactulose, d-xylose, glucose), which when degraded by bacteria produces an increase in hydrogen in the breath of patients with SIBO. The ingestion of foods like bread, fiber and pasta, smoking, the presence of bacteria in the oral cavity, or lung disease may decrease diagnostic accuracy. The diagnosis is confirmed when the levels of hydrogen in breath are over 10 particles per million (ppm) above the baseline or in 2 consecutive samples during the first 60 minutes of the test if baseline hydrogen levels exceed 20 ppm.

The d-xylose test appears to have better sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of SIBO, as it is primarily metabolized by gram-negative bacteria, the ideal substrate for SIBO.

- Intestinal aspirate and direct culture of intestinal content

Although it is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, it is not commonly used, except in research, and it has its limitations, such as the potential contamination of oropharyngeal flora and the fact that bacteria are sometimes unevenly distributed and content may be aspirated where there are none present.

Treatment: How is SIBO treated?

The main treatment consists of antibiotics aimed at reducing the overgrowth of bacteria. Additionally, in some cases, it is also necessary to treat the diseases associated with nutritional deficiencies (ileitis, colitis, vitamin B12 or vitamin D deficiency).

- Antibiotic treatment

The antibiotic treatment will depend on the type of overgrowth, risk factors, resistances, and possible allergies.

The most commonly used guideline is the use of rifaximin, 400-600 mg 3 times daily for 14 days. Rifaximin is not absorbed into the intestine and is well tolerated.

When the overgrowth is mainly due to methanogenic bacteria, it is recommended to add neomycin, 500 mg 2 times a day.

Other antibiotics used are ciprofloxacin norfloxacin, trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, tetracyclines, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

In some cases, when there is no improvement in symptoms or an early recurrence (before 3 months), a second cycle of antibiotics is needed.

Nutrition also plays an important role, especially when antibiotics are not well tolerated. A lactose-free diet that includes vitamin replacement and the treatment of nutrient deficiencies (magnesium, calcium) is essential when addressing this pathology. In severe cases, elementary diets may be used for 10-14 days.

How do we prevent SIBO?

The main thing is to eliminate the factors that predispose it, such as drugs that decrease motility (opiates, benzodiazepines..) or treat the associated pathologies (diabetes, Parkinson�s, celiac disease…).

Some patients require prophylactic antibiotic treatment. It is reserved for those who have four episodes or more of SIBO in less than a year or who present associated predisposing factors (diverticulosis, short bowel syndrome…).

In these cases, the treatment consists of cycles of antibiotics that are rotated and given 5 days a month.

Other recommended treatments are the use of probiotics or statins, which decrease the production of methane, although their role is not entirely proven.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(2) Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D,Yamada T, Mende DR et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011;29:415-20.