The prostate, the organ that gives men so much grief. Evidence shows that sooner or later, it’ll grow. Can we prevent this without the use of drugs?

It is worth explaining the elements that will induce growth in this gland called the prostate. The best medicine is preventive medicine. Monitoring infections, living a healthy lifestyle, and replenishing those hormones we lose during aging is the right course of action.

Dr. Celia Gonzalo Gleyzes – Neolife Medical Team

Anatomy of the prostate

The prostate is a glandular organ of the male reproductive system. It is chestnut-shaped, located in front of the rectum, behind and underneath the bladder. This organ functions as a secondary bladder that puts pressure so semen may be expelled from the urethra. Moreover, it may close the passage to the bladder to prevent it from releasing its contents during intercourse.

The prostate is connected to the testicles through the vas deferens, which rise above the bladder. It surrounds the first section of the urethra, a tube through which urine and semen circulate to the penis.

It consists of different zones:

- The fibromuscular stroma extends post laterally and forms the capsule.

- The transitional zone, close to the prostate utricle and the periurethral glandular tissue.

- The central zone surrounds the transitional zone.

- The peripheral zone occupies 75% of the total volume.

Androgens: their role in prostate development and growth

The effect of androgens in mesenchymal cells is necessary for the formation of the prostate, but also for its growth. Three growth episodes are distinguished: the first occurs in the fetal stage, the second during puberty, and the third begins in middle age and is sustained during aging. The first two episodes are associated with increased testosterone.

The male fetus begins to produce testosterone in the eighth week of gestation, reaches a peak in the 16th week (adult-like concentration) and then decreases to low levels at birth. A short time after birth, testosterone increases again for six months and then drops to undetectable levels during childhood.

The androgenic environment is responsible for the differentiation of the male reproductive system (internal and external), including the prostate. Differentiation and prostate growth begin at week 10-12 of gestation and are considered complete at birth.

What is truly striking, with respect to other organs, is that the prostate continues to grow in adulthood. In the third phase of growth, the transitional zone increases in size, and this time, there is no testosterone spike but quite the opposite: the levels drop.

Lower testosterone and prostatic hyperplasia during aging

Intraprostatic androgen levels in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia are no different than those in unaffected patients.

Testosterone is converted into estradiol through the enzyme called aromatase.

Two estrogenic receptors (ER-alpha and ER-beta) are expressed in the prostate. ER-alpha is detected in stromal cells, and when stimulated, it is associated with hyperplasia and inflammation. By contrast, inactivation of the ER-beta receptor leads to hyperplasia. Prostate stromal cells also express GPR30 and GPER receptors. Their stimulation is caused by an increase in the inflammatory state (mediated by estrogen).

The role of estrogen in the genesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia continues to be studied. Only a few research studies have found a link between elevated estrogen levels or a high estrogen/androgen ratio and benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia, urinary symptoms, and inflammation

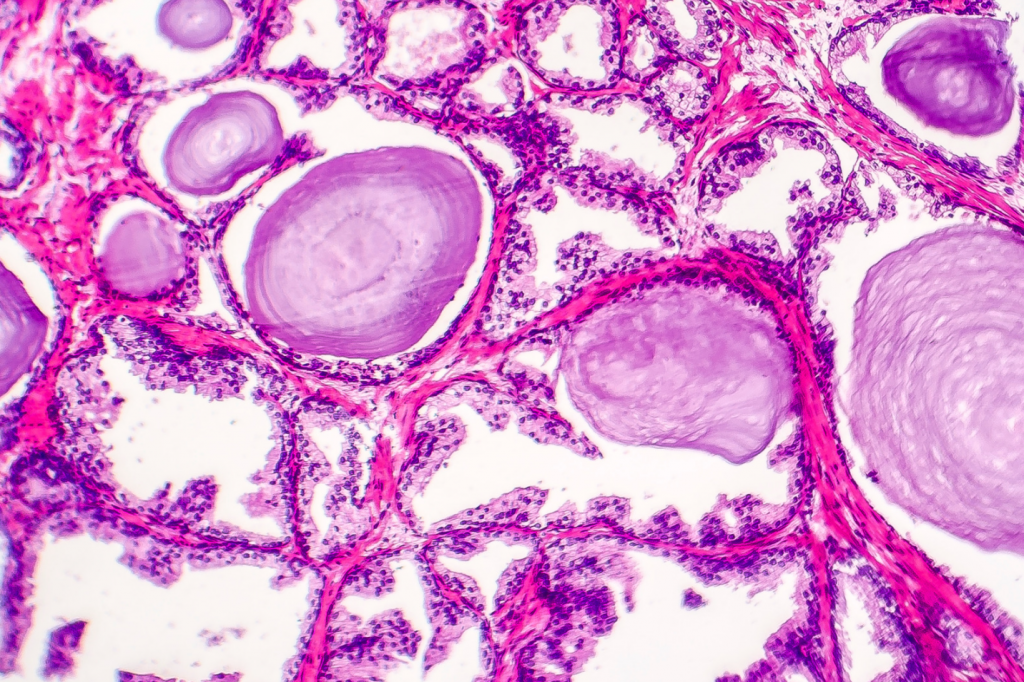

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is defined as the hyperproliferation of the stromal component, and to a lesser extent, of the epithelial component of the prostate. That causes the gland to increase in size. Prevalence increases with age, reaching 40-50% of males aged 50-60 and 80-90% of men over 80 years of age.

Although the diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia is histological (tissue sample), a diagnosis of presumption is usually made with the help of clinical data (lower urinary tract symptoms-LUTS) and by examination (digital rectal exam). Benign prostatic hyperplasia may be asymptomatic but the risk of discomfort also increases over time. Prostate growth puts pressure on the urethra and bladder, making it harder to urinate and empty the bladder. In very severe cases, hydronephrosis (reflux to the kidneys and ureteral dilation) may occur.

The prostate is characterized by an organized immunocompetent system that includes lymphocytes, macrophages, and granulocytes (the prostate-associated lymphoid tissue or PALT). A man’s genitourinary system is exposed to different bacterial infections, which can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. The PALT will be activated when there is a prostate infection. Chronic inflammation is accompanied by the secretion of interleukins, present in advanced stages of benign prostatic hyperplasia. This way, chronic infectious stimulus triggers a cascade of immune events that cause hyperplasia in the prostate stroma.

Patients with prostatitis have a greater number of clostridium and bacteroides compared to healthy men (these are predominantly lactobacilli and staphylococcus). This dysbiosis is thought to perpetuate inflammation.

Metabolic disorders

Epidemiological studies have found a link between patients with disorders in their glucose metabolism/hyperinsulinism and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Low HDL cholesterol and high triglyceride levels have also been shown to be associated with larger prostate volumes.

We are talking about associations based on observational studies that serve as the basis for developing hypotheses, but it is true that inflammation is a fundamental element in the genesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia, and this low-grade inflammatory state is typical in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Everything seems to fit.

A hyperestrogenism that is secondary to metabolic disorders (for example, obesity hypogonadism) modifies the ratio between testosterone and estradiol (T/E2), which leads to the expression of different genes in the prostate. A low T/E2 ratio is associated with an increase in the expression of numerous cytokines and markers of cell immunity activation.

Low testosterone

Low testosterone is a risk factor for the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia and urinary system symptoms. The mechanism by which low testosterone promotes BPH is still being studied, but this hormone is known to work by modulating the inflammatory and immune response in prostate tissue (1).

Summary of preventive measures in benign prostatic hyperplasia

The above mentioned mechanisms and pathological hypotheses lead us to make specific recommendations to prevent the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia, namely the following:

- Treating subclinical/clinical prostate infections (prostatitis)

- Weight management, avoiding overweight and obesity

- Maintaining acceptable levels of visceral fat

- Doing physical activity on a regular basis

- Management of metabolic disorders (dyslipidemia and insulin resistance/prediabetes/diabetes)

- Ensuring adequate testosterone levels (diet and hormone replacement under medical supervision).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Rastrelli G, Vignozzi L, Corona G, Maggi M. Testosterone and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(2):259-271. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.10.006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30803920/