Lack of physical activity has been recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the factors most associated with increased mortality in our society.

This is due to the close relationship between a sedentary lifestyle and the onset of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, obesity or diabetes. It is shown that if we get sedentary patients to start exercising regularly, we can significantly reduce the number of patients who will eventually develop an aging-related disease.

Dr. Moisés De Vicente – Neolife Medical Team

The relationship between physical activity and health is evident

Aging is becoming (in fact it already is) one of the main problems both at the population and individual level. To give us an idea of the magnitude of the problem, it has been estimated that by the year 2024 more than 20% of the world’s population will be over 65 years old (1). As a result, diseases that are directly related to this stage of life will see an upturn, especially neurodegenerative-type diseases.

Dementia is actually a malfunction of neurons or the interconnections between them. As a result, the patient experiences deterioration of their cognitive capacity, which is usually characterized by memory lapses and attention deficit, progressing rather quickly to the point of not being able to perform basic activities such as getting dressed, grooming, or holding a conversation. Figuring out how this phenomenon of neurodegeneration occurs is essential to finding solutions to the phenomenon.

What has been clearly established is that there are a number of risk factors for the appearance of cognitive impairment. Some are impossible to modify, and this has to do with our genetic make-up. However, there are other modifiable factors we can act on.

These factors are educational level, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, hearing loss, smoking, depression, social isolation and physical exercise (2).

Specifically, lack of physical activity has been recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the factors most associated with increased mortality in our society. This is due to the close relationship between a sedentary lifestyle and the onset of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, obesity or diabetes. In fact, it is shown that if we get sedentary patients to start exercising regularly, we can significantly reduce the number of patients who will eventually develop an aging-related disease.

Thus, the relationship between physical activity and health, both physical and mental, is evident. However, the key mechanism responsible for the relationship between physical activity and cognitive health is currently unknown. It likely depends on multiple interrelated and complementary factors.

As is well known, cognitive functions that have to do with things learned a long time ago, such as talking, recognizing objects or people, are the functions that are slowest to deteriorate in patients as they get older. Activities that have to do with the acquisition and processing of new knowledge and resolving problems are the ones that first get damaged with age. Fortunately, this damage is usually manifested in a generalized way, though there are exceptions, resulting in a slowing-down of our actions or decision-making, which does not usually influence our day to day as older people (3). In most cases, patients virtually remain in this situation indefinitely. However, others experience more advanced cognitive impairment, even presenting true dementia eventually.

It has been shown that patients who reported minor cognitive changes that are typical of aging and are usually related to short-term memory loss markedly improved by regularly performing physical aerobic exercise for 12 weeks (4). In fact, by adopting this measure these patients presented a decrease in the markers of silent inflammation, such as C-reactive protein. It has been suggested that this silent inflammation may be one of the etiopathogenic mechanisms for the onset of cognitive impairment (5).

A recently published study (6) describes how structured and collective physical activities provide greater benefit to older people. These include aerobic-style exercise, like Thai Chi and even muscular resistance activities, and preferably those accompanied by a friend or partner. This last factor is key to achieving greater consistency with exercise as opposed to exercising alone, for example (7).

And how much physical exercise is necessary to prevent the onset of dementia? The recommended amount and type of exercise to obtain proper cardiopulmonary health is well documented. In the case of cognitive health, however, it’s not entirely clear. This is because studies conducted to obtain this information come up against a problem: not all elderly patients are able to perform similar physical activities. What does seem clear is that some kind of physical activity should be done. Probably it should be adapted to the clinical and social situation of each patient.

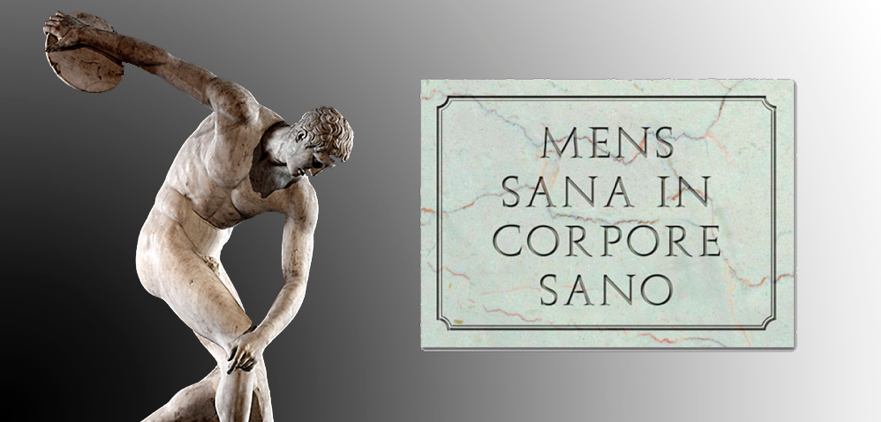

We can conclude that it is important to have and perform adequate brain gymnastics to maintain good cognitive health. But it is also essential to adopt a series of physical exercise routines that will help us maintain excellent cognitive activity and prevent its deterioration. The saying “Mens sana in corpore sano” has never rung truer.

At Neolife we base our treatment program on eight fundamental pillars: nutrition, nutritional supplementation, metabolic and hormonal equilibrium, sleep and oxidative stress, regenerative medicine , detox and behavioral health and physical exercise. We believe that a good exercise routine adapted to the situation of each patient allows us to preserve our cognitive health and avoid or at least delay the onset of cognitive decline.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Statistics Canada. Canada’ s population estimates: Age and sex, July 1, 2015. 2015;1–5. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/150929/dq150929b-eng.htm

(2) Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 6736(17):62.

(3) Harada CN, Natelson Love MC, Triebel KL. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013; 29(4):737–52.

(4) Kamegaya T; Long-Term-Care Prevention Team of Maebashi City; Maki Y, et al. Pleasant physical exercise program for prevention of cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly with subjective memory complaints. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012; 12(4):673–9.

(5) Hess NC, Smart NA. Isometric exercise training for managing vascular risk factors in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017; 9:1–12.

(6) Amanda V. Tyndall; Cameron M. Clark; Todd J. Anderson; David B. Hogan; Michael D. Hill; R.S. Longman; Marc J. Protective Effects of Exercise on Cognition and Brain Health in Older Adults. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2018;46(4):215-223.

(7) Tyndall AV, Davenport MH, Wilson BJ, et al. The brain-in-motion study: Effect of a 6-month aerobic exercise intervention on cerebrovascular regulation and cognitive function in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2013; 13(1):1–10.