Classically, medicine has refrained from intervening, indicating that we must accept certain limitations that age imposes on us and considering this deterioration as something normal.

Some will say that this seeking to be optimal is not a question of health, but rather of “doping” or a “flight forward”, but make no mistake, no one is talking here about participating in an Olympics… We’re talking about aging with a good quality of life. In addition, there are myths in classical culture that have an impact on prejudices and trends when it comes to learning to diagnose and treat hormonal deficits, dismissing them without knowing the scientific evidence behind the treatment.

Dr. Iván Moreno – Neolife Medical Team

Decline in hormone values

In this series of articles we are reviewing the different reasons why the use of testosterone is not widespread despite showing benefits in numerous studies.

In the first part of this article we talked about the progressive decline in hormone values in both men and women with age, and how their replacement led to improvement on several levels (metabolic, vitality, muscle mass, etc.). Also in the previous issue we commented on the consequence of not considering aging to be a disease, and that of the reactive approach adopted by medicine, in contributing to the use of testosterone not becoming more widespread.

In this new issue we’ll examine the importance of understanding the difference between the normal and the ideal in medicine, as well as the role played by the myths that surround hormones, both in the general population and among doctors.

“The Normal” (the statistical fallacy that condemns us all to deteriorate equally)

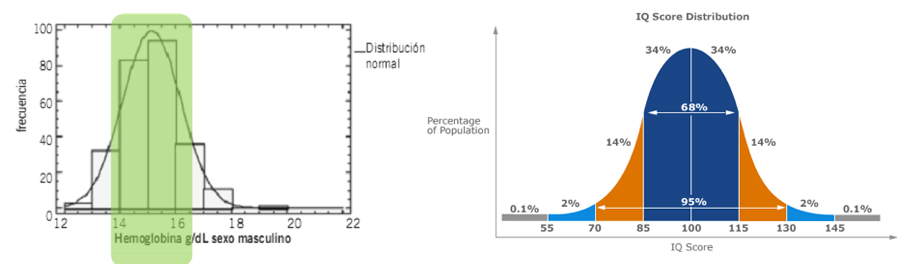

Biology and medicine look for reference levels in the population for eachbiomarker (height, fasting glucose, vitamin D levels, etc.). Each variable we measure tends to group naturally around central values in what we call a “normality curve“. Classically speaking, an interval around the mean, approximately 70% central, is considered normal.

As we age, our comparison group changes, so the hormone levels or bone density of a 55-year-old person can be much worse than the ones he had at 35 years of age and still be considered “normal”.

Paradoxes of “normal”:

- At 35 it’s normal to be well.

- At 55 it’s “normal” to have less testosterone and muscle mass.

- At 75 it’s “normal” not to be able to exercise or walk.

- At 85 years it’s “normal” to break one’s hip after a casual fall.

We’re condemned to deteriorate due to the very way we define normal values!

This apparent normality means that we don’t feel the urgency to change, and we’re content to be within “normal” values, while we deteriorate little by little.

Our calm complacency is only broken when we meet people who, by training and taking care of themselves, or by being particularly balanced at a hormonal level, show us that there is another way to age,with a much better physical and mental condition, which should be the normal one.

Exercise and diet always work. There are studies, even in people in their nineties, that show that, with the right stimuli, the body always responds.

There is increasing scientific evidence pointing to the benefit of replenishing our hormones. To demonstrate this, we will comment on a real case from Neolife:

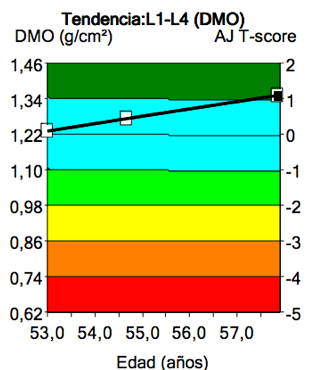

The “normal” thing is to lose bone density over the years, right? Perhaps some lucky ones may keep their bone, but… gaining bone over the years?

In the graph we can see how, over the years, with adequate supplementation, hormone replacement, diet and exercise, this patient is strengthening his bones.

Classically, medicine has refrained from intervening, indicating that we have to accept certain limitations that age imposes on us, and considering this deterioration as something normal. Some will say that this seeking to be optimal is not a question of health, but rather of “doping” or a “flight forward”, but make no mistake, no one is talking here about participating in an Olympics… We’re talking about being able to continue playing tennis at 60, being able to go out on the streets and have a social life at 70-80 or having the strength to live independently into our 90s. We’re talking about aging with a good quality of life. Are we really going to avoid using a tool that has been shown to be effective and safe when used correctly?

The myths (in general culture… and also among doctors)

Hormones, and specifically testosterone, have acquired a bad reputation. This is mainly due to the fact that side effects from other types of treatment have been attributed to it, for example:

- Those produced by the use of synthetic anabolic steroids that cause liver and cardiovascular damage.

- Treatments with testosterone at extremely high doses in bodybuilding, which can produce aggressiveness and changes in the voice.

- Sex change treatments, in which very high doses are used precisely to achieve some of these side effects (virilization, changes in the voice or in hair distribution, etc.).

These myths have an impact on prejudices and tendencies when learning to diagnose and treat these relative hormone deficits, both in lay people and in professionals, who often reject it without knowing the scientific evidence behind the treatment.

In short, two of the factors that prevent the correct use of testosterone becoming widespread:

- Assuming that normal deterioration over the years is the best we can expect, only because statistically it’s what happens to the majority.

- Accepting beliefs and false rumors about hormones that have become established either due to the misuse or abuse of these or of chemical products deriving from them.

In the final chapter of this series we will discuss two other factors, in this case those that are purely in the medical field: the lack of medical expertise in the management of hormones to improve patients, and low-quality clinical studies which are subsequently misinterpreted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) PhD RCR, MD FW, MD HMB, MD HP, MD EJHM, MD MM, et al. Quality of Life and Sexual Function Benefits of Long-Term Testosterone Treatment: Longitudinal Results From the Registry of Hypogonadism in Men (RHYME). J Sex Med. Elsevier Inc; 2017 Aug 2;14(9):1–12.

(2) BCGP BRWP, BCGP JSCPC. Hormone Replacement. Primary Care Clinics in Office Practice. Elsevier Inc; 2017 Sep 1;44(3):481–98.

(3) Dhindsa S, Ghanim H, Batra M, Kuhadiya ND, Abuaysheh S, Sandhu S, et al. Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism and Their Reduction After Testosterone Replacement in Men With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015 Dec 22;39(1):82–91.

(4) Schiffer L, Kempegowda P, Arlt W, O’Reilly MW. MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: The sexually dimorphic role of androgens in human metabolic disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Jul 10;177(3):R125–43.

(5) Bianchi VE, Locatelli V. Testosterone: a key factor in gender related metabolic syndrome. Obesity Reviews. 2018 Jan 21;19(4):557–75.

(6) Corona G, Dicuio M, Rastrelli G, Maseroli E, Lotti F, Sforza A, et al. Testosterone treatment and cardiovascular and venous thromboembolism risk: what is ‘new’? J Investig Med. BMJ Publishing Group Limited; 2017 Aug;65(6):964–73.

(7) Kaplan AL, Hu JC, Morgentaler A, Mulhall JP, Schulman CC, Montorsi F. Testosterone Therapy in Men With Prostate Cancer. European Urology. European Association of Urology; 2015 Dec 21;69(5):1–10.

(8) Lopez DS, Qiu X, Advani S, Tsilidis KK, Khera M, Kim J, et al. Double trouble: Co-occurrence of testosterone deficiency and body fatness associated with all-cause mortality in US men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017 Nov 20;88(1):58–65.

(9) Morgentaler A. The Testosterone Trials: What the Results Mean for Healthcare Providers and for Science. Curr Sex Health Rep. Current Sexual Health Reports; 2017 Oct 31;9(4):1–6.